The Treasury has further work underway on the topic of culture to help clarify the key components of culture that are particularly relevant to individual and societal wellbeing.

Disclaimer

This paper is part of a series of discussion papers on wellbeing in the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. The discussion papers are not the Treasury’s position on measuring intergenerational wellbeing and its sustainability in New Zealand.

Our intention is to encourage discussion on these topics. There are marked differences in perspective between the papers that reflect differences in the subject matter as well as differences in the state of knowledge. The Treasury very much welcomes comments on these papers to help inform our ongoing development of the Living Standards Framework.

Formats and related files

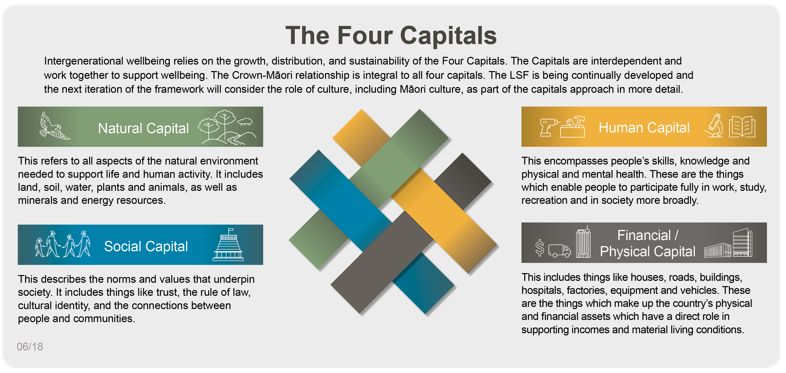

The Treasury's Living Standards Framework (LSF) aims to maximise intergenerational wellbeing by putting sustainable, or intergenerational, wellbeing at the core of policy development and evaluation. The LSF distinguishes between current wellbeing and the sustainability of current wellbeing outcomes, which is represented by four capitals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 - The four capitals in the Treasury’s LSF

The work on current wellbeing captures people’s quality of life and their ability to live a life they have reason to value in the present. It covers a wide range of financial and non-financial wellbeing outcomes, such as jobs, income and wealth, health and education outcomes, social connections and environmental quality. In contrast, the four capitals represent the key productive resources that are required to “produce” human wellbeing. The four capital stocks thereby focus our attention on our ability to sustain current wellbeing levels into the future, emphasising the Treasury’s longer-term perspective on managing New Zealand’s assets.

As some capital stocks (particularly Financial/Physical and Natural capital) depreciate with use, careful trade-offs need to be made between current wellbeing and the four capitals.

The LSF indicators for current wellbeing and the four capital stocks help inform these complex trade-offs by helping policy-makers take into account the range of impacts that a policy option may have on the factors that affect New Zealanders’ wellbeing, now and in the future. The underlying principle of the capital’s framework is that good public policy enhances the capacity of natural, social, human and financial/physical capital to improve wellbeing for New Zealanders.

The role of culture in the Living Standards Framework#

Wellbeing is closely linked to culture. A common question with regard to the LSF is therefore where culture fits within the framework. This question is particularly pertinent within the New Zealand context. As Smith (2018, p. 14) has noted: “As both a bicultural country (reflecting the Treaty of Waitangi) and a multicultural country (with an immigrant background), issues of culture, belonging and identity are of fundamental importance if a wellbeing framework is to work in New Zealand.” The Treasury therefore has further work underway on the topic of culture to help clarify the key components of culture that are particularly relevant to individual and societal wellbeing.

These components of culture may be considered within two areas. The first relates to ethnicity and culture and this will be considered briefly below. This conversation acts as an introduction to a series of Discussion Papers, which are forthcoming, and will cover culture from Māori, Pasifika, and Asian perspectives. The second relates to cultural artifacts and includes fine arts. This area is less-developed within the LSF at this time and will be considered in more detail later.

Culture is a broad concept with a wide range of meanings, which tend to be less well-defined than other areas of wellbeing. At a high level, culture refers to the ways we see and represent ourselves in relation to others, including both our sense of commonality as well as our sense of difference. Two key streams of work related to culture as part of the LSF include:

- Assessing and ensuring the cross-cultural validity of the LSF

- Clarifying the importance of culture for individual and societal wellbeing.

This background note outlines current and future work by the Treasury in both these areas.

1. Assessing and ensuring the cross-cultural validity of the LSF#

Given the cultural diversity within New Zealand society it is critical to make sure that New Zealand's different cultural perspectives are incorporated into the LSF conceptual framework as well as its dashboard of indicators, to ensure their meaningfulness and relevance across the different cultures in New Zealand society. So far, work within the Treasury has focused on assessing the conceptual validity of the LSF from Te Ao Māori, Pacific and Asian worldviews. Future work in this area will aim to extend these insights by considering the diverse experiences of the many peoples who have come to New Zealand.

2. Clarifying the importance of culture for individual and societal wellbeing#

The importance of culture as a factor shaping individual and societal wellbeing has been recognised throughout the work on the LSF. For example, in their proposed indicator framework for measuring current wellbeing, King, Huseynli, and MacGibbon (2018) specifically recommended the addition of a cultural identity dimension to the LSF framework for current wellbeing, which was adopted from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2011, 2013): “The inclusion of this dimension within the wellbeing framework recognises the importance of a shared national identity and sense of belonging, and the value of cultural, social and ethnic diversity. It recognises New Zealand is a multicultural society, while also acknowledging that Māori culture has a unique place” (King et al., 2018, p. 6).

However, despite the recognition of the importance of culture in determining wellbeing, currently no clear framework exists for the relationship between culture and individual and societal wellbeing outcomes. Therefore, work is underway to develop an overarching and comprehensive framework that clarifies the role of culture in influencing individual and societal wellbeing. At this stage, the following components of culture are recognised to be important in the context of the LSF:

- Cultural identity and diversity. As Smith (2018, p. 25) has noted: “The ability to live as who you are, without feeling compelled to adopt another identity to fit in with wider society, is an important aspect of wellbeing, as is having a sense of belonging and connection to a culture and place.” Cultural diversity carries benefits for wider societal wellbeing also; for example, by providing access to overseas networks and market knowledge, new markets and local products, providing multiple perspectives on problem solving and expertise in cultural protocols and intercultural competency (Statistics New Zealand, 2009). The importance of cultural identity and diversity also features in the independent proposal for the Living Standards Dashboard, which includes “the proportion of the population who feel able to be themselves in New Zealand” as one of its indicators (Smith, 2018, p. 25).

- Cultural activities and participation. In terms of cultural participation, two different types of culture are commonly distinguished (eg, see Statistics New Zealand, 2009; Throsby, 1997; Williams, 1998). The first common definition, which is here referred to as “lived culture”, defines culture as the set of attitudes, beliefs, practices, values, shared identities, rituals, customs and so on, which are common to a group, whether the group is delineated on geographical, ethnic, social, religious or any other grounds (Throsby, 1997; see also, Hawkes, 2001, p. 3). A second definition refers to culture as “embodied culture” (Allan, Grimes, & Kerr, 2013), that is, cultural activities, such as arts, theatre and music, and the products of these activities. It includes high-culture, which was historically identified by the intelligentsia or a status class of a society, such as classical music or opera, but also popular culture, that is, cultural products such as music, art, literature, fashion, dance, film and television programming that are consumed by the majority of a society’s population.

- Cultural competences. Cultural competences are those capacities that enable people to access the deeper meanings of their culture and to maintain and transfer their cultural knowledge for the benefit of future generations. For example, language is a critical cultural competence that enables the understanding of cultural rituals and traditions, enables their continued practice and their transfer to future generations. We note that the independent proposal for the Living Standards Dashboard includes “the number of Māori language speakers” as one of its indicators (Smith, 2018, p. 25).

- National identity. National identity refers to people's sense of cohesiveness as being New Zealanders, which transcends cultural diversity within New Zealand. The Start of a Conversation on the Value of New Zealand's Social Capital (Frieling, 2018) has described how, for the wellbeing of society, it is important that people do not only identify with others in their own personal networks or those who are similar to them, but also experience a wider sense of community and belonging to the overall society. This more encompassing national identity creates an openness to others in society and encourages collaboration across different social groups. National identity also features in the independent proposal for the Living Standards Dashboard, which includes an indicator on “the proportion of the population feeling a strong sense of belonging in New Zealand” (Smith, 2018, p. 25).

- Cultural artefacts and heritage. Cultural heritage includes the objects and sites of cultural importance that signify the shared history of New Zealanders. Their preservation demonstrates a recognition of the importance of the past and of the things that tell its story to future generations.

As the Treasury's LSF develops we will need to clarify the unique contributions of the different components of culture to individual and societal wellbeing in New Zealand, as well as the ways they might be affected by relevant trends. For example, New Zealand culture is influenced by the diverse origins of its population, which is projected to become more ethnically diverse (Statistics New Zealand, 2017).Another trend that may influence New Zealand’s culture is climate change and the possible large-scale migration flows into New Zealand owing to the effects of sea-level rise on New Zealand’s surrounding Island populations.

The Treasury will be looking for internal and external contributions to the upcoming discussion papers to further reflect on the topic of culture from different angles.

References#

Allan, C., Grimes, A., & Kerr, S. (Motu Economic and Public Policy Research). (2013). Value and culture: An economic framework. Wellington: Manatū Taonga - Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

Hawkes, J. (2001). The fourth pillar of sustainability: Culture's essential role in public planning. Melbourne: Common Ground Publishing.

Frieling, M.A. (2018). The start of a conversation on the value of social capital. Wellington: The Treasury.

King, A., Huseynli, G., & MacGibbon, N. (2018). Wellbeing frameworks for the Treasury. Office of the Chief Economic Adviser Living Standards Series: Discussion Paper 18/01. Wellington: The Treasury.

OECD. (2011). How's life? Measuring well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2013). How's life? 2013 measuring well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Smith, C. (2018). Treasury Living Standards Dashboard: Monitoring intergenerational wellbeing. Wellington: Kōtātā Insight.

Statistics New Zealand. (2009). Culture and identity statistics domain plan draft for consultation. Wellington: Author.

Statistics New Zealand. (2017). National ethnic population projections: 2013 (base) - 2038 (update). Wellington: Author. Accessed on 28/05/2018, from http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalEthnicPopulationProjections_HOTP2013-2038.aspx

Throsby, D. (1997). The relationship between cultural and economic policy. Culture and Policy, 8(10), 25-36.

Williams, R. (1998). Cultural theory and popular culture. A reader. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press.